Film Analysis and Review

Goodbye Golovin opens with a quiet tension: Ian is on the cusp of departure. The film does not dramatize his grief; instead it lets silence, ambient texture, and the weight of place speak. In its brief runtime Grimard captures a man who wants more but cannot outrun himself.

There is something deeply poetic in how Ian’s voice-over works. It is not explanatory but confessional, a continuous thread that binds internal longing with external action. His narration reveals the burden of this decision: leaving is not freedom unless you understand what holds you back. The voice-over is well balanced: not overpowering the images, but often acting as contrapuntal commentary, questioning his own motives as he crosses dusty streets, stirs in dim interiors, and pauses between buses.

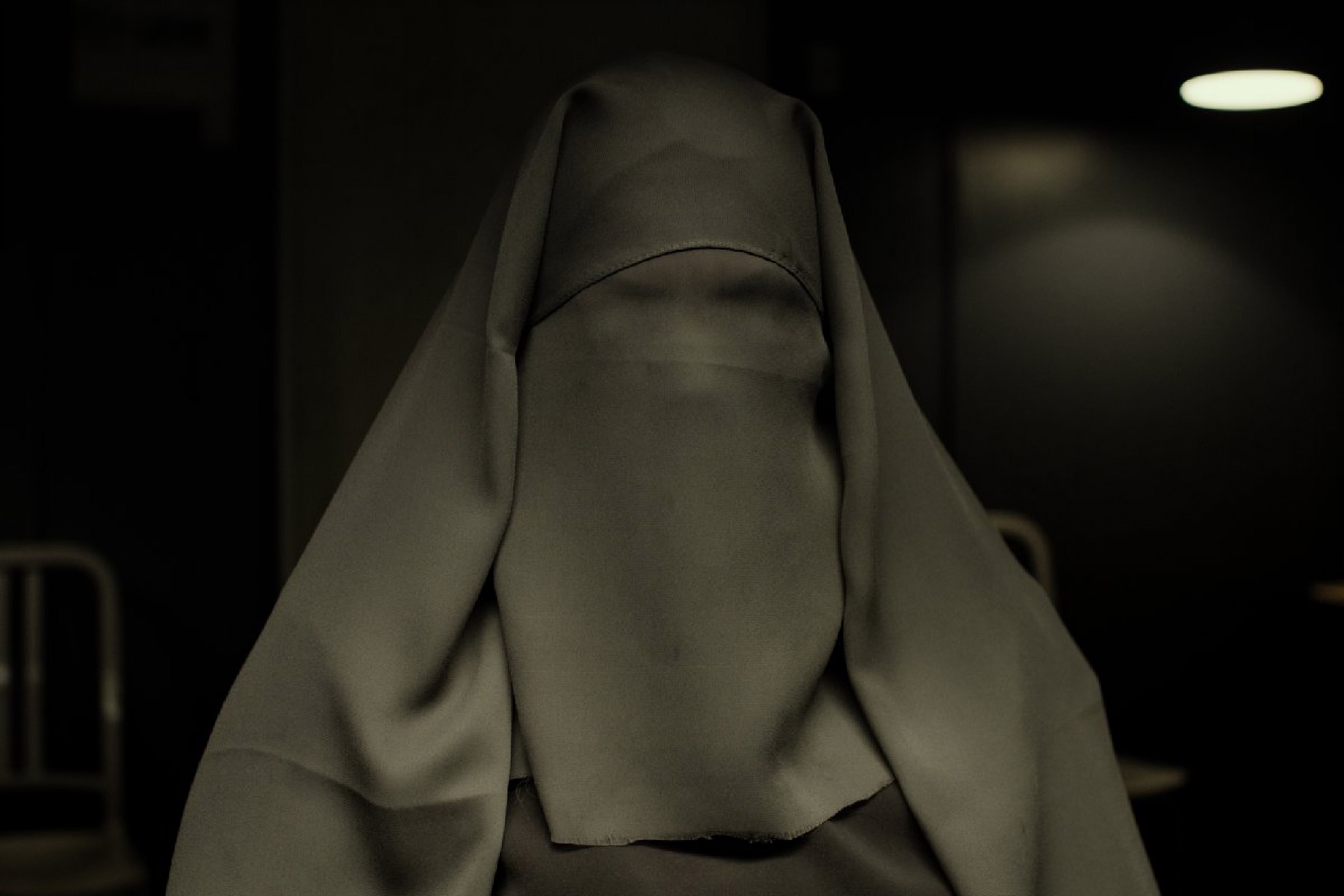

Visually the film leans on monochrome or desaturated hues and natural light. Cinematographer Ariel Méthot Bellemare frames Ian often in rectangles of windows, doorways, corridors — boundaries that seem to hem him in even as he moves. The urban architecture, brutalist housing blocks, narrow alleys, and concrete façades feel like characters themselves, reflecting the stagnation he wants to escape. In some moments Ian’s body is dwarfed by the built environment; in others, tight interiors close in on him, communicating claustrophobia.

The pacing is deliberate. Some cuts linger beyond what feels comfortable. These hesitations allow emotional shadows to accumulate. Grimard resists ornamental flourish. He allows emptiness to weigh. When Ian walks, when he lingers in rooms, when he watches his own reflection—these moments become part of the emotional architecture.

What stands out is how little the film offers catharsis. The final act is not a dramatic break but a series of small reckonings. A chance encounter with his sister’s roommate tethers him back, reminding him that we cannot shed life as easily as luggage. The film concludes not with a triumphant departure but with the question of what one carries when leaving. It asks whether changing the location changes the self.

This is not a political documentary about Ukraine or Soviet legacy. It is a human story. Grimard resists grand statements. He captures the internal geography of exile, belonging, and yearning. Critics of the film’s festival screenings have noted this quiet ambition: it “connects everyday life and politics,” offering “a sense of life and allows us to feel.”

Some viewers have treated the film as cinematic poetry. A Letterboxd summary puts it simply: “For Ian Golovin the death of his father is the chance at a new life outside his native country … he is forced to face his decision — why he is always blindly moving forward and what he is leaving behind.” The film’s festival reception bears that: it garnered honorable mentions at Berlin Generation 14plus and the Abitibi‑Témiscamingue festival, and won the Grand Prize at Plein(s) écran(s).

Oleksandr Rudynskyi gives a performance of subtle gravity. He is not given grand speeches or emotional outbursts; he is given stillness and distance, and from that the film draws its power. His ambivalence—between wanting to leave and wanting to stay—is the film’s emotional crux.

What the film teaches is that departures are never clean. What remains behind whispers louder than what lies ahead. Goodbyes are loaded. Departures are haunted. And in that haunted space Grimard finds his film.

Filmmaker Insight and Production Context

Mathieu Grimard grew up in Montreal but felt a pull back to his roots and personal stories of dislocation. He was inspired by a documentary in i‑D Magazine about young Ukrainians seeking freedom after the Maïdan revolution. The theme of leaving and belonging resonated personally: Grimard has Ukrainian roots and in his twenties he felt the tension between staying home and seeking opportunity abroad. In his words the story started when he wrote what might have happened if he had tried to leave.

Though the film is set in Ukraine, Grimard did not intend to make a political film. He wanted to keep it human. He avoided naming Kiev or overt references to current events. Instead he sought universality: leaving a place and being haunted by it.

Production was swift: shot over three days using natural light. Grimard emphasized improvisation even as he meticulously planned locations, gathered photographic references, and created a shot list. The narrative is simple—to leave or not—but the emotion had to feel true. The editor (also Grimard) worked deeply to find rhythm, trimming what felt excess and allowing silence and pause to breathe.

Casting Oleksandr Rudynskyi was challenging partly due to language: their communication required a line producer to act as interpreter between the director and actor. Yet Rudynskyi understood Ian inherently. Grimard credits his performance as central to the film’s emotional gravity.

Though the film touches on grief and flight, it was always intended as a character study. Grimard avoided superfluous subplots. He said mistakes in early drafts taught him the value of paring down. The film is small in scale but vast in interior dimension.

In the Q&A he’s noted that he’s planning new projects which may evolve into series exploring youth, roots, and identity.

For Filmmakers Lessons from Goodbye Golovin

Departures are emotional: let the silence do the work.

Narration can complement rather than explain: use voice-over as internal counterpoint.

Let architecture mirror interior states: frames, corridors, thresholds matter.

Pacing is atmosphere: delays, hesitation, space can build tension as much as action.

Simplicity is strength: avoid excessive plot clutter in favor of emotional coherence.

Let the climax reframe rather than resolve: endings need not tie loose ends—sometimes they only reveal what remains.

Verdict

Goodbye Golovin does not give a grand escape. It gives a quietly aching question: where do you go when escape is not enough? In fourteen minutes Mathieu Grimard delivers a film that feels both intimate and expansive, anchored by a performance that whispers more than it shouts. This is short film cinema with integrity—lean, haunted, precise.

⭐ Curated Shorts Pick

Silent strong unforgettable

.jpg)